Breadcrumb

- Home

- Conditions & Treatments

- Kyphosis

What is kyphosis?

Kyphosis is an abnormal forward curve in the upper spine. Children with kyphosis have a rounded or "hunchback" appearance. While some children are born with kyphosis, most cases develop during adolescence.

Some degree of front-to-back curve of the spine is normal and healthy. However, if a child’s spine curves forward 50 degrees or more, they should be seen by a spine specialist.

Most cases of adolescent kyphosis are mild. A teen with kyphosis should be closely monitored by a doctor until they have stopped growing. Many will not require treatment. If the forward curve becomes severe, it can lead to pain and deformity that can compress the lungs and interfere with breathing. Severe kyphosis can only be corrected with bracing and may also require surgery.

Kyphosis and spine anatomy

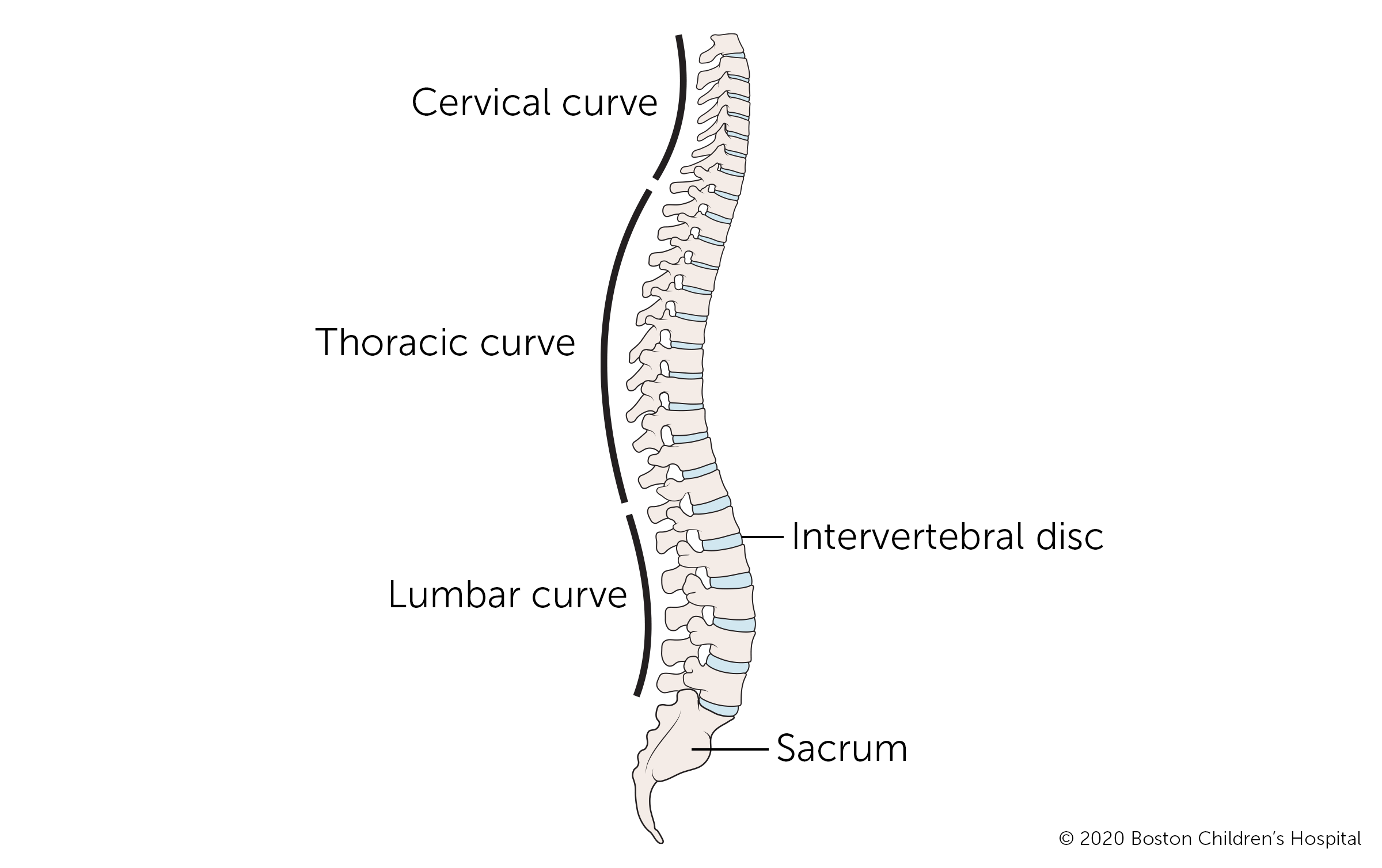

To understand kyphosis, it helps to understand the structure of the spine. The spine is made up of individual bones, called vertebrae, that are joined together by muscles and ligaments. Our ability to bend and twist our backs come from the fact that vertebrae are separate. Flat, soft discs cushion the vertebrae and prevent them from rubbing against each other.

Together the vertebrae, discs, muscles, and ligaments make up the vertebral column that protects the spinal cord from the base of the spine all the way up to the brain.

The regions of the spine have specific names:

- Cervical spine refers to the neck region.

- Thoracic spine refers to the upper back.

- Lumbar spine refers to the lower back.

Kyphosis typically develops in the thoracic region of the spine. In rare cases, it can occur in the cervical spine.

What are the different types of kyphosis?

Different types of kyphosis have different causes and become noticeable at different stages of physical development. (The conditions below do not include kyphosis related to trauma, infection, bone cancer, or other disorders.)

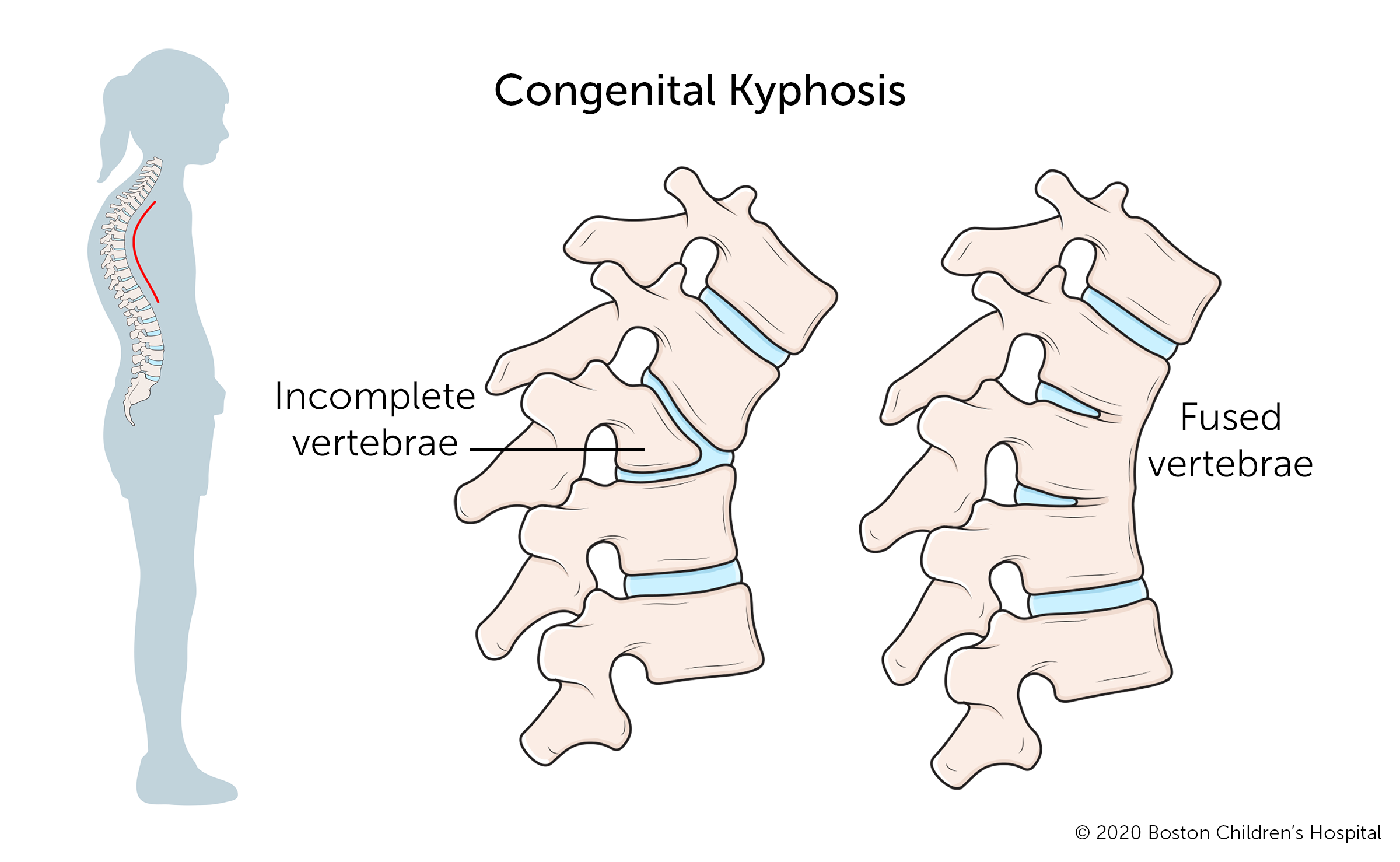

Congenital kyphosis

Children with congenital kyphosis are born with the condition, though it may not be noticeable immediately at birth. The deformity happens when a child’s spinal column does not develop properly in the womb.

Congenital kyphosis often causes compression of the spinal cord and usually gets worse as the child grows. Many children with congenital kyphosis need spine surgery at some point during childhood or adolescence.

Postural kyphosis

Postural kyphosis is the most common, and usually least serious, type of kyphosis. It becomes noticeable in adolescence. Poor posture, including slouching in front of a computer for long periods, can increase the risk that a child’s spine and surrounding muscles will not develop properly.

Postural kyphosis is not a structural deformity, not painful, and most often does not get worse over time. The forward curve is rounded. If asked to stand up straight, a teen with postural kyphosis can do so.

Physical therapy, and in some cases, bracing, can correct the muscular and structural imbalance in the back.

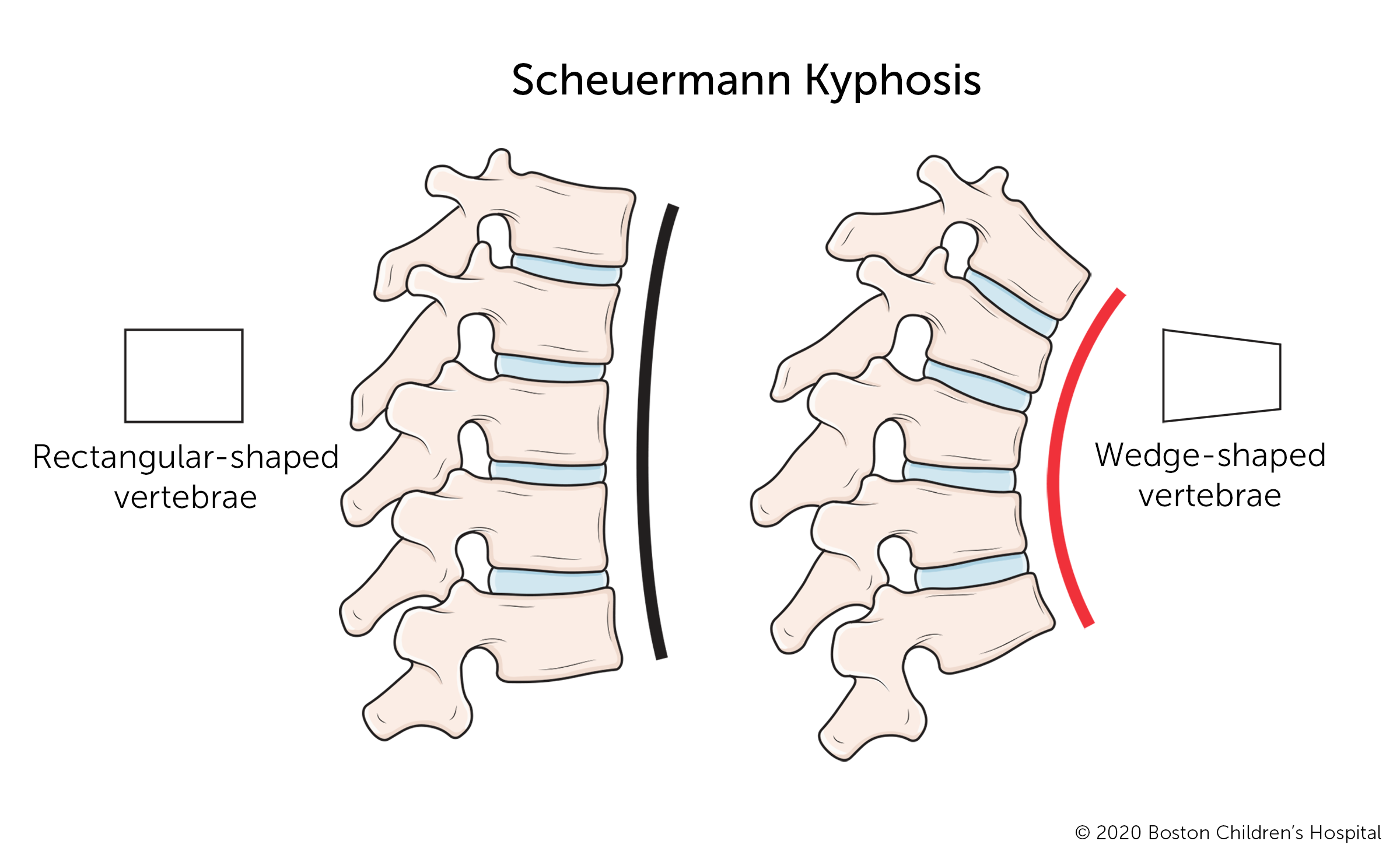

Scheuermann’s kyphosis

Scheuermann’s kyphosis is usually more severe, more rigid, and more deforming than postural kyphosis. Also known as juvenile kyphosis, it is a structural abnormality that occurs when several vertebrae in the thoracic spine develop a triangular (rather than rectangular) shape. The wedge-like shape causes the spine to bend forward at a sharp angle. A teen with Scheuermann’s kyphosis cannot correct their curve by trying to stand up straight.

Scheuermann’s kyphosis typically becomes noticeable in early adolescence and continues to progress as long as the child continues growing. In severe cases, this type of kyphosis causes back pain that gets worse after sitting or standing for long periods. Activity can also be painful. Correcting severe cases of Scheuermann’s kyphosis usually requires bracing, and possibly surgery. Typically, orthopedic surgeons delay surgery until after the child has reached their full height.

What are the possible kyphosis complications?

Many children with kyphosis have no complications. For other children, kyphosis progresses and becomes worse over time. If it does progress, the forward curvature can become painful and interfere with lung function. In rare cases, it may also interfere with your child’s eating, making it hard to swallow and possibly causing acid reflux. If your child has kyphosis, it’s very important to have regular check-ups. A spine specialist can monitor the spinal curvature and intervene if it is progressing.

Is it possible to prevent kyphosis?

Just as kyphosis often has no definite cause, there is no sure way to prevent the condition. If you are pregnant or could become pregnant, proper nutrition, prenatal care, and vitamins (especially folic acid) may help reduce the risk of your child being born with congenital kyphosis or other birth defect. If your family has a history of kyphosis, consult a geneticist.

Symptoms & Causes

What are kyphosis symptoms?

Some kyphosis symptoms are visible to the naked eye. Other symptoms are not visible but can make a child with kyphosis uncomfortable.

Visible kyphosis symptoms include:

- Visible hump, typically in the upper back

- Upper back appears higher than normal when bending forward

- Head always or almost always bent forward

- Excessive rounding of the shoulders

- Difference in the height or position of the shoulders or shoulder blades

Children with severe kyphosis may have one or more of the following symptoms:

- Tight muscles in the backs of their thighs (hamstrings)

- Back pain and stiffness

- Trouble breathing

- Extreme fatigue

What causes kyphosis?

Kyphosis can be caused by different things. In many cases, the exact cause is not known.

One type, Scheuermann’s kyphosis, tends to run in families. Other types of kyphosis can be caused by neuromuscular conditions such as cerebral palsy or spina bifida. Spinal infections and tumors can weaken the vertebrae, causing the spine to collapse forward. Treatments for spinal tumors, including chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery, can also lead to kyphosis.

Factors that increase a child’s risk of developing kyphosis include:

- Poor posture (slouching)

- A family history of spine problems

- Neuromuscular conditions, like spina bifida, cerebral palsy, osteogenesis imperfecta, and muscular dystrophy

- Metabolic conditions, such as diabetes

- Trauma resulting in a spinal fracture that goes untreated or heals poorly

- Spinal infections such as osteomyelitis

- Spinal tumors, either cancerous or benign

Diagnosis & Treatments

How is kyphosis diagnosed?

Most cases of kyphosis are detected by parents, a pediatrician, or during a school screening. Early detection and follow-up are important for successful treatment. If your child has kyphosis, whether confirmed or suspected, they should be seen by an orthopedic specialist (orthopedist). The orthopedist will ask about your child’s medical and family histories, perform a physical exam, and measure the curve. They may order diagnostic tests to determine the nature and extent of your child’s kyphosis.

The first diagnostic test for kyphosis is usually an X-ray to measure and evaluate the degree of spinal curvature. This measurement will help determine what treatment your child needs to control or correct their kyphosis.

Other diagnostic testing might include:

- CT or CAT scan (computerized tomography scan), which uses a combination of X-rays and computer technology to produce cross-sectional images of the body with detailed images of bones, muscles, fat, and organs. Images from a CT scan are more detailed than images produced by an X-ray.

- MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) uses a combination of large magnets, radiofrequencies, and a computer to produce detailed images of organs and structures within the body. MRIs take longer than CT scans but produce more detailed images that can help identify or rule out spinal cord and nerve abnormalities.

- A bone scan is an imaging test that uses dye to identify any degenerative or arthritic changes in the joints, detect bone diseases and tumors, and determine the cause of bone pain or inflammation. It can also help identify or rule out infection or fractures.

- Blood tests are sometimes used to look for associated metabolic conditions. They are not a standard part of diagnosing kyphosis, however.

- Pulmonary function tests may be used to test your child’s lung function if their breathing is affected. This is not a standard part of diagnosing kyphosis, however.

How is kyphosis treated?

Kyphosis treatment depends on the complexity and severity, as well as your child’s age and stage of physical development.

The goals of kyphosis treatment are:

- To stop the progression of kyphosis in children who are still growing

- To prevent further deformity

- To correct spinal deformity in adolescents and young adults who have reached their full height

Non-surgical treatments for kyphosis

The majority of children with postural and Scheuermann’s kyphosis do not need aggressive treatment. Their treatment may include observation and monitoring, physical therapy, and possibly bracing.

Observation and monitoring

Even if your child is diagnosed with kyphosis, their spine may not curve any further. However, kyphosis can become more severe during periods of rapid growth. As your child grows, they need to be monitored through regular visits with an orthopedist. Their risk for developing severe kyphosis slows and eventually stops after puberty.

Physical therapy

Physical therapists provide exercise regimens and therapies to address the muscular imbalance associated with kyphosis. Exercises can help strengthen your child's core, upper back, shoulders, and shoulder blades.

Bracing

If your child has moderate or severe kyphosis and is at an early stage of growth, their doctor may prescribe a brace. Several factors will determine the most effective type of brace and amount of time your child should wear it, including the severity of their curve and their stage of growth. The brace holds your child's spine in a more upright position while they grow. This can partly correct the curve and prevent it from increasing.

- Bracing helps improve posture and function.

- Bracing can help control or correct curves.

- A successful bracing program may help your child avoid surgery.

The success of bracing depends on how well your child follows the custom regimen developed for them by their orthopedic doctor. Typical braces are the Boston Kyphosis brace (developed at Boston Children's Hospital) and the Milwaukee brace.

Surgical treatment for kyphosis

Spinal fusion surgery is the most common surgical procedure for treating severe cases of kyphosis. The surgeon will stabilize the curved section of the spine with instrumentation (rods and screws) and place bone grafts between the damaged vertebrae. This stimulates new bone growth so the vertebrae fuse into solid bone.

For young children who are still growing and require surgery, surgical options may include:

- Dual posterior growing rods (MAGEC rods) is a technique that uses extendable rods that are inserted into a child’s back to control the progression of spinal curvature. The rods are lengthened periodically to allow continued spinal growth.

- Expansion thoracostomy/VEPTR™ is a titanium rib implanted into a child’s back and chest to control the progression of chest and spinal deformity, while allowing growth of both the chest and the spine.

Your child may need kyphosis surgery if:

- Their curve measures 75 degrees or more

- Bracing proves unsuccessful at slowing or stopping the curve from progressing

- Your child has congenital kyphosis involving skeletal malformation (surgery may be needed at an early age)

- The kyphosis is caused by an infection or tumor

What is the long-term outlook for children with kyphosis?

When treated successfully, kyphosis can be corrected, and children go on to lead active, unrestricted lives. If your child needs surgery, they should be able to walk around in a few days and return home in about a week. They can go back to school within a month or so, and resume most activities within three to four months. Complete fusion takes about one year.

How we care for kyphosis at Boston Children’s Hospital

The Spine Division at Boston Children’s Hospital is the largest and busiest pediatric spine center in the United States. Our spine specialists see thousands of patients and perform hundreds of surgeries each year. We collaborate regularly with the Department of Neurosurgery to provide safe, customized care for even the most complex spine problems. For children with an injury or deformity of the neck or upper spine, Boston Children’s also offers the Complex Cervical Spine Program. Our Spine and Sports Program treats spine conditions and injuries that affect the young athlete.