Breadcrumb

- Home

- Conditions & Treatments

- Aortic Valve Stenosis

What is aortic valve stenosis?

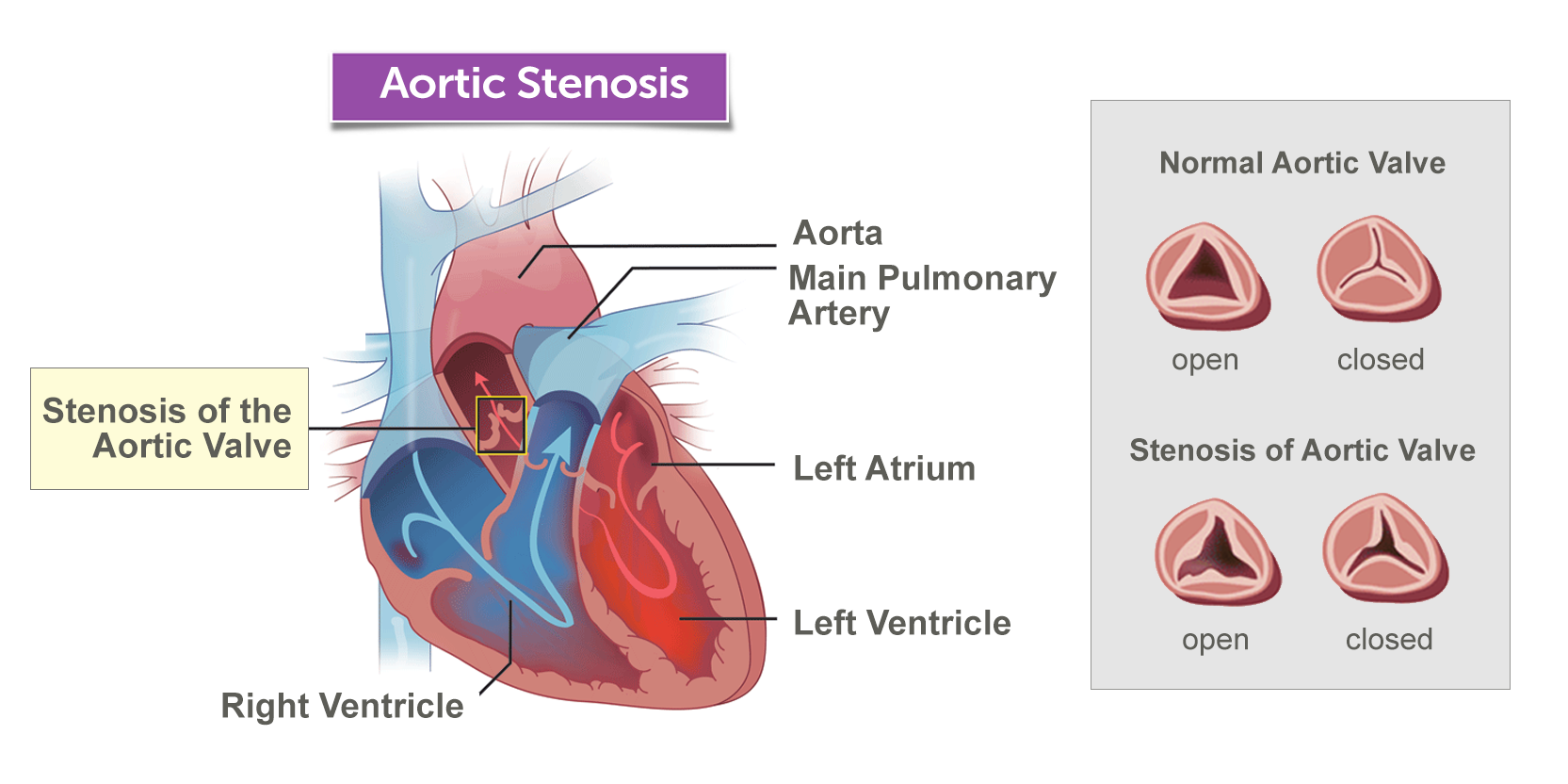

The term “stenosis” describes an abnormal narrowing within a structure of the body. Aortic valve stenosis, therefore, refers to the narrowing of the heart’s aortic valve, a one-way valve located between the left ventricle — the pump that pushes blood out to the body — and the aorta, the major blood vessel that carries blood to different parts of the body.

When a child has aortic valve stenosis, the leaflets (tiny flaps of tissue) that make up the aortic valve get stuck and can’t separate fully. This causes a problematic blockage that increases the pumping work of the left ventricle, and may lessen the amount of blood that goes out of the ventricle to the body through the aortic valve. This extra work can weaken the heart over time.

Some children with aortic valve stenosis don’t need immediate treatment, and those with no outward symptoms can do very well for a long time with only regular monitoring by their care team. However, children with more advanced aortic valve stenosis are likely to require interventional catheterization, valve repair, or replacement surgery.

What are the types of aortic valve stenosis?

The condition is classified according to its severity: mild, moderate, severe, or critical.

Mild aortic valve stenosis

A child with mild aortic valve stenosis has very limited narrowing within the valve. These children will not show any outward symptoms; the only detectable problem is a pronounced, easily identified heart murmur. Children with this mild type of aortic valve stenosis are otherwise healthy and able to go about their daily lives without disruption.

Moderate aortic valve stenosis

Children with moderate aortic valve stenosis have a slightly more significant narrowing of the aortic valve, but usually show no outward symptoms and are otherwise healthy. A child with this type will have an easily detected and identified heart murmur.

Severe aortic valve stenosis

A child with severe aortic valve stenosis has such an advanced degree of narrowing in the valve that the left ventricle may become very stiff and may not function properly. Interventional catheterization with balloon dilation or valve repair or replacement surgery are necessary to treat severe aortic valve stenosis.

Critical aortic valve stenosis

This, the most serious type of aortic valve stenosis, is usually present at birth. The newborn’s aortic valve is so narrowed that the heart cannot pump enough blood to nourish the body, so immediate intervention is needed — usually by interventional catheterization with balloon dilation or by surgically replacing the aortic valve.

Symptoms & Causes

What are the symptoms of aortic valve stenosis?

Many children with aortic valve stenosis show no outward symptoms when they are in the mild to moderate stages of the condition. Usually, the only identifiable symptom in these cases is a pronounced heart murmur.

As aortic valve stenosis progresses, children may experience:

- Chest pain

- Shortness of breath or difficulty breathing with exercise

- Irregular heartbeat or heart palpitations

- Chest pain

- Dizziness during or immediately after physical activity

- Fatigue

- Less ability to exercise

- Fainting

You should seek treatment from a qualified medical professional right away if you notice any of these warning signs in your child.

What causes aortic valve stenosis?

Aortic valve stenosis is normally caused by a birth defect, such as:

- A narrowed aortic valve

- A condition called a bicuspid aortic valve, meaning that the child is born with an aortic valve that has only two leaflets instead of the usual three

- Valve leaflets that are fused together

- Valve leaflets that are unusually thick and do not open all the way

Aortic valve stenosis can also be caused by rheumatic fever, a complicated and rare disease that can develop in children who have an infection of streptococcus bacteria, like strep throat or scarlet fever.

Rheumatic fever can lead to scarring of the tissue in the aortic valve, causing the valve to become constricted and narrowed. This scarring can also increase the likelihood of calcium deposits building up along the valve — a major risk factor for aortic valve stenosis in adulthood.

Diagnosis & Treatments

How is aortic valve stenosis diagnosed?

Diagnosing aortic valve stenosis usually involves several steps. Often, a clinician will first notice that your child has a heart murmur, a telltale noise blood makes as it flows from the left ventricle to the aorta.

Heart murmurs can be detected with a stethoscope during a routine physical examination or with an electrocardiogram (EKG or ECG). Sometimes, the murmur may emerge when the child is being tested or treated for another condition altogether.

The loudness of the murmur, the location in the chest it is best heard, and the types of noise it causes (such as gurgling or blowing) will all give your child’s clinician a better idea of the nature of your child’s heart problem.

Although exams and electrocardiograms can suggest the possibility of aortic valve stenosis, an echocardiogram is the definitive test used to confirm the diagnosis.

Other tests your child’s clinician might order to make, or rule out, a diagnosis of aortic valve stenosis can include:

- Chest X-ray

- Electrocardiogram (EKG or ECG)

- Cardiac catheterization

- Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

How is aortic valve stenosis treated?

Your child's exact treatment plan will be determined by age, the extent of narrowing in the aortic valve, and overall health.

Monitoring

Children with mild to moderate aortic valve stenosis may not require any treatment other than routine monitoring in the short term. Your child's cardiologist will regularly evaluate your child for any sign of further narrowing in the aortic valve and related complications. Most often, routine monitoring will involve physical examinations and echocardiograms.

Medication

Medication is not a cure for aortic valve stenosis, but it can be helpful in managing specific symptoms. In some cases, your child's clinician may prescribe medication to:

- Help the heart maintain healthy function and blood flow

- Control blood pressure

- Prevent abnormal heart rhythms, called arrhythmias

A child with aortic valve stenosis may also need to periodically take antibiotics to prevent an infection called bacterial endocarditis, even if the aortic valve has been surgically replaced. Bacterial endocarditis can cause serious damage to the inner lining of the heart and its valves. You should always let medical personnel know about your child's aortic valve stenosis before making arrangements for a medical procedure, even if the procedure seems minor or unrelated to your child's cardiac care.

If your child has aortic valve stenosis, but no other cardiac problems, antibiotics will likely not be needed before a routine dental procedure, such as teeth cleaning.

Interventional catheterization/balloon valvuloplasty

Interventional catheterization is a minimally invasive procedure. During a catheterization, a thin tube, called a catheter, is threaded from a vein or artery into the heart. This catheter can be used to fix holes in the heart, open narrowed passageways (like the aortic valve), and create passageways.

Recognizing the benefits of this minimally invasive treatment — less discomfort, shorter recovery periods, and the use of the child's own valve, which will grow with the child after the procedure — Boston Children's considers interventional catheterization the preferred frontline approach to aortic valve stenosis.

The most common interventional catheterization procedure used to treat aortic valve stenosis is balloon dilation, also known as balloon valvuloplasty. While the child is under sedation, a small, flexible catheter is inserted into a blood vessel, most often in the groin. Using tiny, highly precise cameras and tools, clinicians guide the catheter up into the inside of the heart and across the aortic valve. A deflated balloon at the tip of the catheter is inflated once the tube is in place, and this balloon stretches the aortic valve open, reversing the problematic narrowing.

Valve repair or replacement surgery

For children with severe aortic valve stenosis, balloon valvuloplasty may not adequately fix the narrowed valve and restore healthy heart function. In other cases, as the child grows, an aortic valve that was previously treated successfully with one or more balloon-dilation procedures may begin to narrow again, adding strain to the heart and affecting blood flow throughout the body. Repair or replacement of the aortic valve is the next step in treatment for these children.

For all patients, we make every effort possible to repair the aortic valve. This may involve leaflet sculpting (valvuloplasty) or leaflet replacement. Boston Children’s has extensive experience with the latest advances in aortic valve repair, including the Ozaki procedure.

When repair is not possible, cardiac surgeons will remove the damaged aortic valve and replace it with a mechanical or tissue valve. Mechanical valves can last for more than 20 years before needing to be replaced. There is a small risk of blood clot formation associated with mechanical valves, so typically children are prescribed a blood-thinning medication to prevent complications. Tissue valves do not require the same blood-thinning medication, although they may not last as long as mechanical valves.

Another valve-replacement option is to replace the aortic valve with the child’s own pulmonary valve (Ross procedure). This approach avoids the need for blood thinners.

When valve replacement is necessary, the valve selected will be based on the individual needs and circumstances of the child. All types of valve-replacement surgery have excellent success rates and a low incidence of complications. Children who have valve-replacement procedures are likely to enjoy normal, healthy lives with minimal to no restrictions on playing sports or engaging in other activities. Most children need to stay in the hospital for a week to 10 days after valve repair or replacement surgery and will return to their normal activities quickly.

How we care for aortic valve stenosis

The Boston Children's Hospital Benderson Family Heart Center team has years of expertise in treating all types of heart defects and heart disease, with specialized understanding of problems like aortic valve stenosis that affect the valves of the heart.

We treat every stage of aortic valve stenosis in children, adolescents and adults, as well as babies in utero in our Fetal Cardiology Program. We use minimally invasive techniques whenever we can and are committed to repairing a child's own valve rather than resorting to an entire valve replacement whenever possible.